This is a deep dive in payment for developers. The purpose of this rather lengthy article is to show in a very simple way how payment works, while always relating and linking it to the overal progress in technology: servers and security. Fintech and payment is my personal passion and for many years I have been working with teams, business people, tech founders, banks, regulators, international companies and I feel I have a thing or two to help developers with. It is also intended for this guidline to work particularly well for backend and servers developers since I believe majority of complexity lies in there. You will see lots of graphs and I’d highly recommend you to click on them to enlarge them and look at them thoroughly. I have came to realize, personally, sometimes a picture is worth a thousand words. Another angle that this article is trying to push for is “learning by example”. We are following a practical approach with less focus on jargons and theory, and more on the whys and hows. Working with noebs, an open source payment gateway has also left us with a solid open source foundation and ready codebases that curious developers can tap into for even more practical examples. The intention was never to write a book, that would never be possible for my time and resources. Another consideration (reads big catch) is that I deliberately dropped citation and referneces. Usually that is a big red flag, but in my defence I was eager to get a first publishable draft out of my way; and with the advent of chatbots and AI, it became practically trivial to throw in the whole text to any free chatgpt-ish service and ask it for resources. But mostly it was for my personal convenience: listing and citing resources would have added a considerable burden on me that I just was not able to do. Lastly, I wrote this preface after I finished a draft version of this article, so there’s that.

I also included some examples and extensive set of graphs. Example codes listed herein were mostly for my own preferences too, since calculating luhn number was something I recall I never encountered doing, and the elegancy of the solution caught and triggered the nerd in me. But again, the intention was never to have an amalgamation, but rather just to show bits and pieces from here and there.

Use Public Key Cryptography

Remember, security is a complex field that often involves balancing the needs of the system, including performance and usability

Before we jump directly into what PKC is, why and how to use it. Let’s explain all of the approaches first and from there we can conclude why our recommendation is to deploy Ledger recommends the usage of public key cryptography.

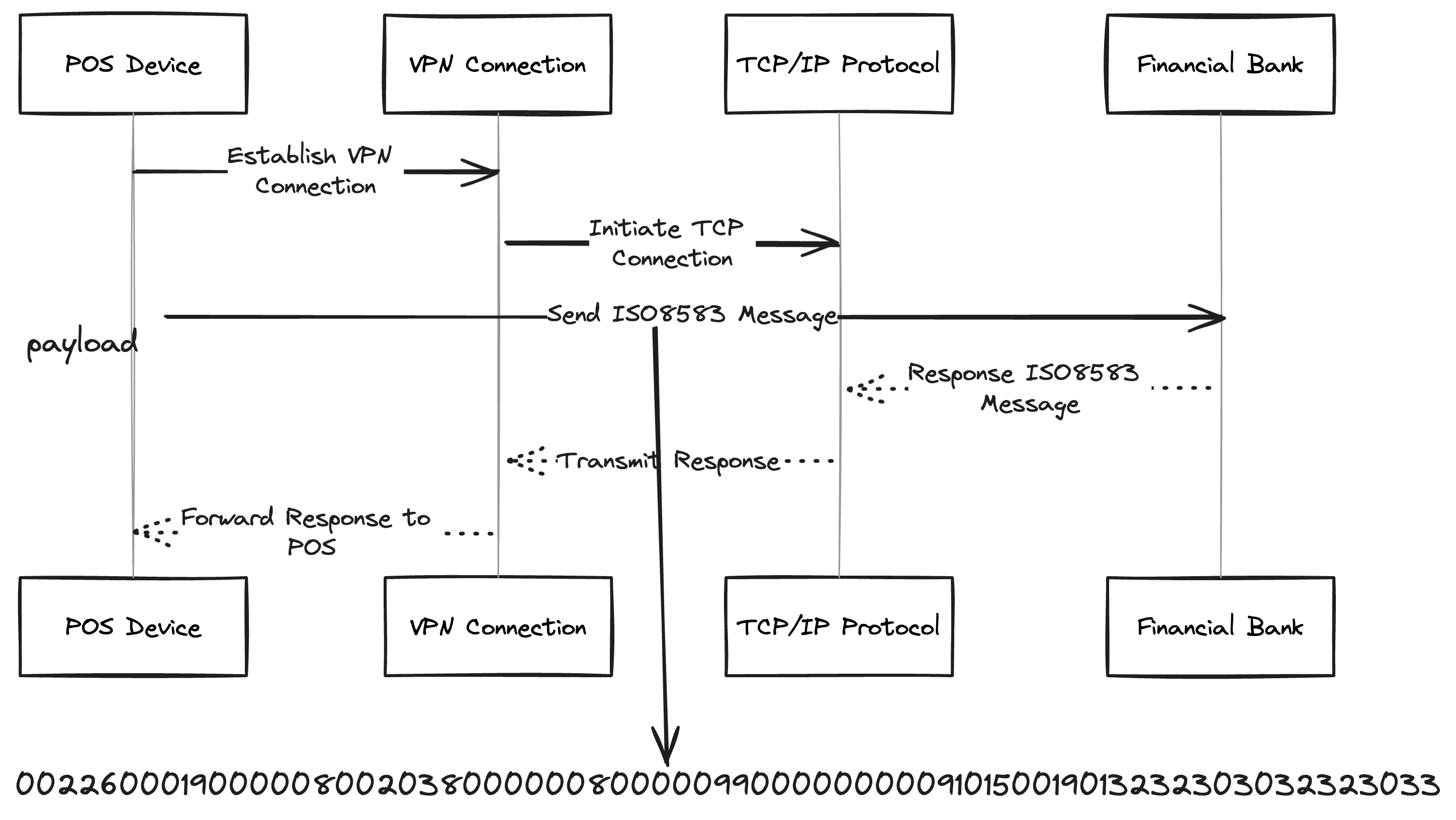

How POS encryption and transactions work

POS usually use these combination of methods for securely communicating with the bank or the payment processor. They may vary between different institutions, but the idea is the same:

- POS connects via a private network, VPN, to the Bank or the payment processor

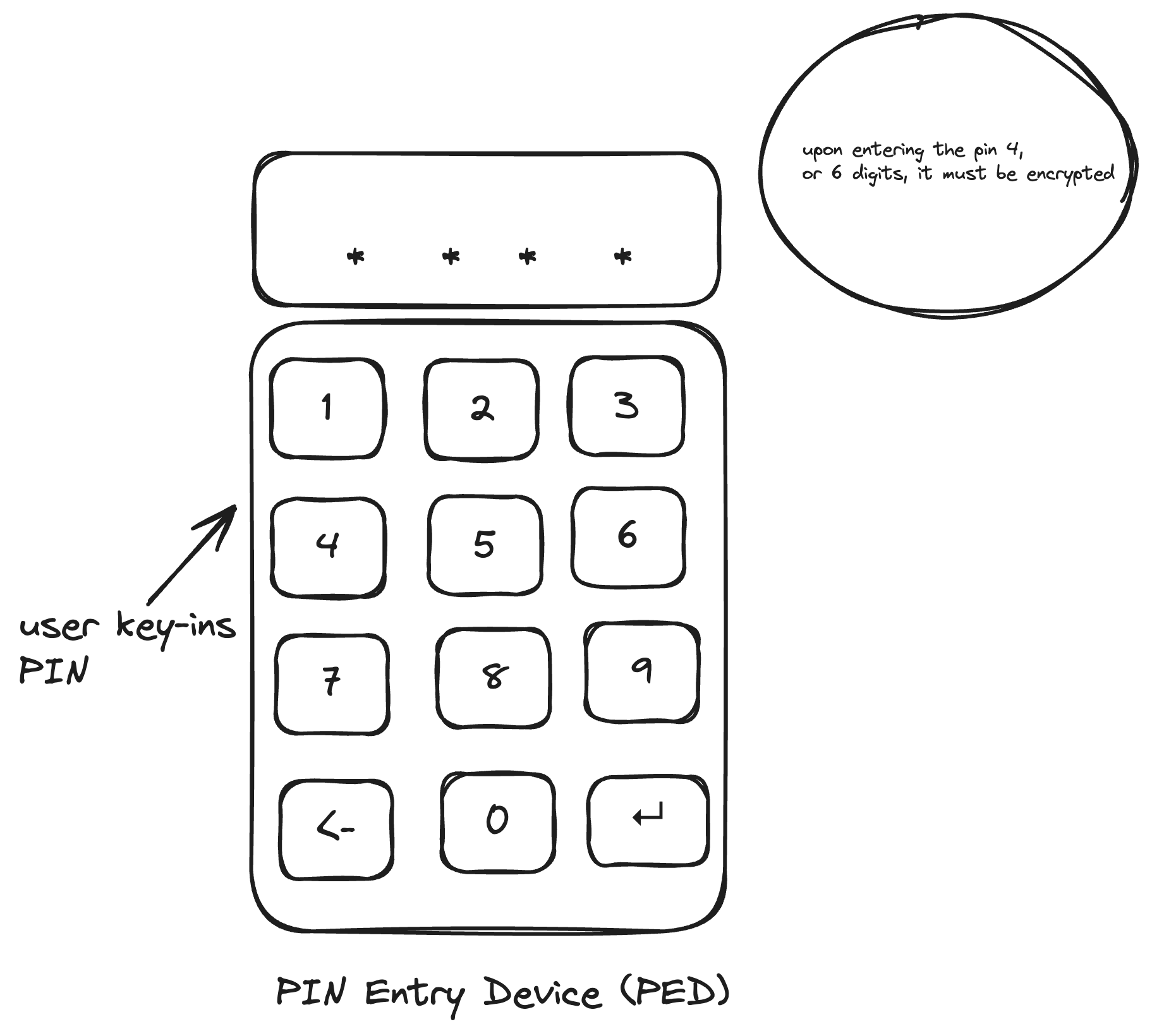

- POS uses a symmetric key to encrypt the PIN, usually DES or 3DES, we call that card present transactions, in that the card itself should phyiscally be present to fullfill the transaction (swipe, chip, etc)

- The communication is usually done via ISO 8583, which is a standard for financial transactions. Sometimes, it is just JSON over HTTPS. ISO8583 is merely just a protcol for laying out the data in a specific way that is easy to parse and understand, a protocol. It does not do any encryption or security by itself.

- The bank or the payment processor decrypts the PIN and processes the transaction, to access the raw PIN and further perform the transactions

We are starting with the POS because it is the most used platform (historically) for performing transactions, and it is legacy enough to steer us and help us set up the stage for whatever we aim to propose. Banks, fintech companies, and regulators have spent huge capital on POS, and it is not going away anytime soon. So, we need to understand how it works so we can be thoughtful about ways to improve it.

ISO8583 is a messaging protocol that defines the data elements and the structure or content of the message exchanged between two financial systems. It doesn’t really specify the underlying protocol: TCP, a full duplex TCP or https, that is an implmentation part and outside the scope of the protocol. There’s a good reason that why ISO8583 still uses TCP and not HTTP: TCP is a full duplex meaning peers (POS, and the acquirer bank) can send / receive requests simulatenously. HTTP follows request / response cycle, in that until after you recieve a response, the POS will be blocking.

I’d advise the readers to look into 1 for a depiction of a tcp connection.

This is pretty much how every POS network operates, and by all means it is a work of art. Elegant and beautifully done peace of system. It doesn’t compromise security for convenience. It is usable and to this day very much in used whenever you swipe your card. Pretty much like HTTP/1.1. Elegant design. But let’s unroll it even further since we are in the business of security, and let’s see what attack vectors we have:

- Level-0 is the VPN network, without that the whole security are bound to collapse

- Level-1 is the symmetric key, which is usually DES or 3DES.

. There are strict requirements when it comes to PED (PIN Entry Device) and the encryptions too imposed by the regulator. Now, the exact way to DES/3DES encrypt a PIN is irrelevant to this article, however we encourage the curious readers to look into our open source repo that shows an implementation in python, Check our open source PIN Block tool, TA. Looking at the code, you can see how one can calculate PIN block using DES (and 3DES), and how the whole system comes in place: the PAN is used to mask the raw pin, whilst in some systems (card personalizations) the pin digits (number of pin: 4 or 6) is embedded in the track 2 info to aim with a more secure PIN encryption.

. There are strict requirements when it comes to PED (PIN Entry Device) and the encryptions too imposed by the regulator. Now, the exact way to DES/3DES encrypt a PIN is irrelevant to this article, however we encourage the curious readers to look into our open source repo that shows an implementation in python, Check our open source PIN Block tool, TA. Looking at the code, you can see how one can calculate PIN block using DES (and 3DES), and how the whole system comes in place: the PAN is used to mask the raw pin, whilst in some systems (card personalizations) the pin digits (number of pin: 4 or 6) is embedded in the track 2 info to aim with a more secure PIN encryption.

It is also super important to visualize the actual process, because payment infrastructure might be so overwhelming that often developers find them obscure to understand. What really happens is the following:

- A terminal POS will send the request, with the sufficient information, including the pan, encrypted pin, expdate, terminal id (super important), transaction amount, system trace audit number

- The payment processor will then lookup the database to retrieve the terminal key via the terminal ID – sometimes the process might be a little bit more involving than that, but the idea is the same: you would still need to lookup the terminal key via a same old database query. We are still doing a regular CRUD here, nothing fancy.

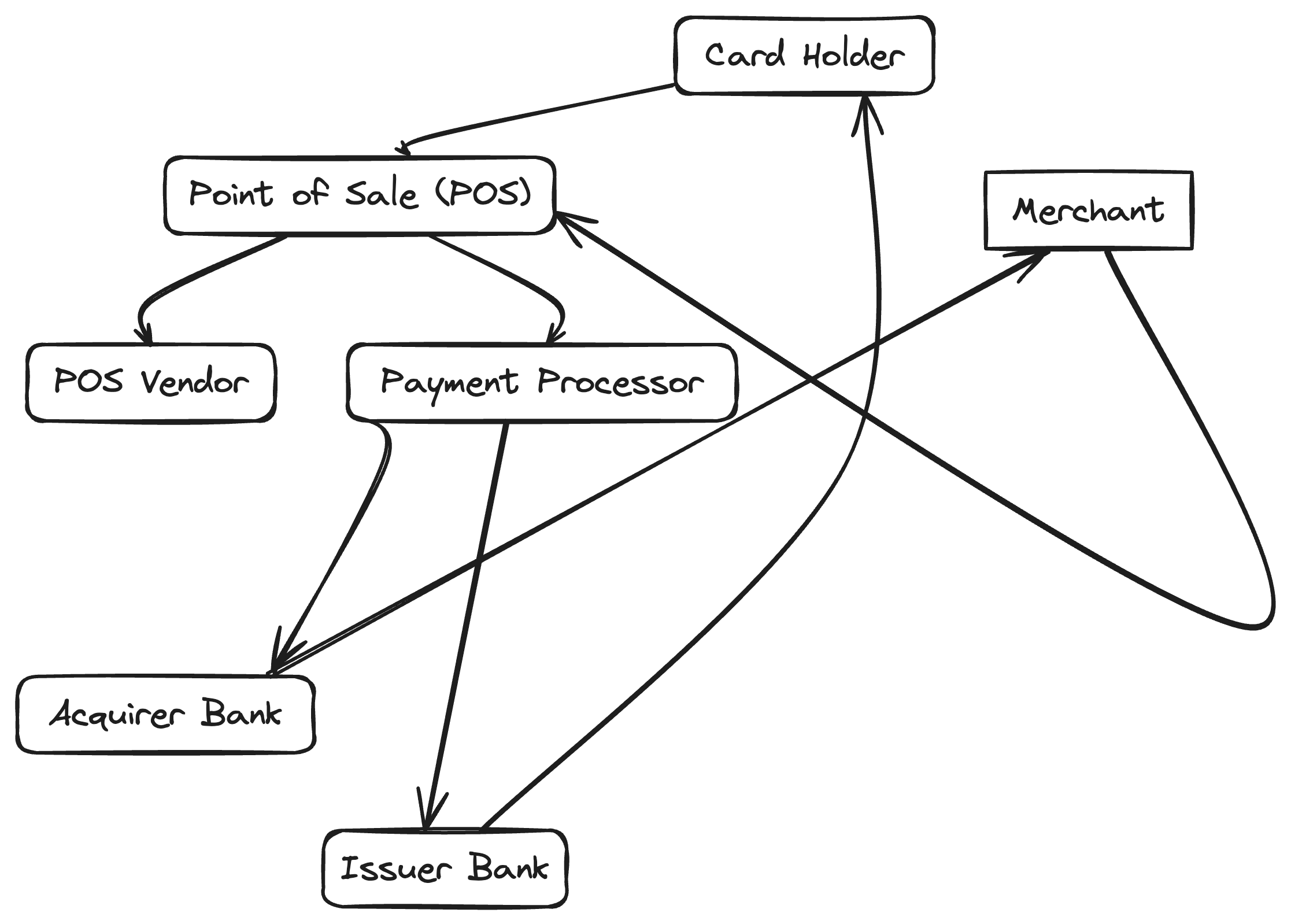

Before we move further, it is important to see the whole picture here and reflect again on the system:

- Each participant is a node in the network, with a responsibility to fullfill.

- PED (like POS) are very crucial in that they are the biggest attack surface to the whole ecosystem, they initiative the transaction, and the encryption happens within them

- The card holder is equally responsible of the safety of their own cards

- Merchants are also well legilible to ensure they are in compliance with procedures for card acceptance. A good scenario to emphasize how this ecosystem plays together is the classical example of “my card was stolen”, and chargebacks. When a cardholder flags a transaction as not authorized, their bank (issuer bank) would hard (they have the incentive) to refund the card-holder. Now, depending on the circumantances, the merchant is weakest link in the chain – and while a $1000 won’t yield the bank bankrupt, it can inflict a considerable damage to the merchant.

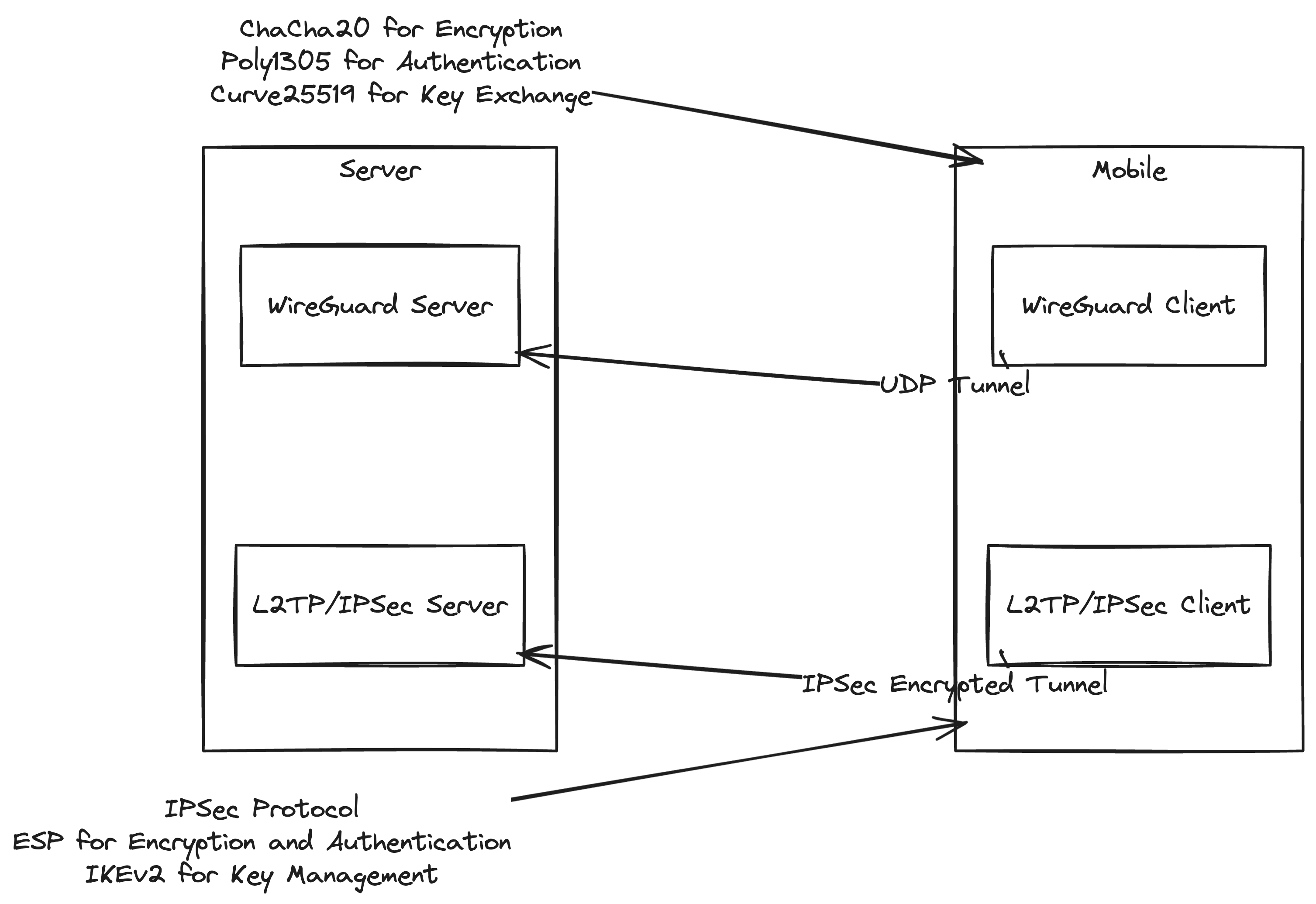

VPN and the private network

A crucial step in the payment is the VPN-protected network access. VPN secures a tunnel of communication, sending tcp requests between two entities. VPN creates a secure connection over a less secure network, that is the internet. VPN is used here to limit the interaction to a handful of entities that are constrained by a different process in the organization: when you want to integrate with say a bank, before you reach the stage of technical integration, you would have to go through a series of processes, including legal, compliance, and business and thorough due dilligence: a) that will mark you as a trusted partner, and b) you can be held accountable for any breach of security. A good thing to remember is that a human process still exists and it is the thin layer between sanity and absolute chaos.

In most of the cases, the industry is still using IPSec with l2tp vpn. The process usually involves sharing a pre-shared key (PSK) between the two parties, and then using that key to establish a secure tunnel. The PSK is usually shared via a secure channel – eg, they will send it over an SMS, some cases involve a physical handover of the key in a CD. And then there are credentials those are the IP of the server and exchange of ports and IPS (source and destination) to white-list the new entity. That’s it pretty much. Another enticing new protocol is wireguard. Wireguard is extremely simple to setup and use (for both server and clients), also modern and built with golang. Has some neat use cases in that they deliver usually kernel-space level of services in a user-space mode. The specifics of wireguard are not relevant to this article, but we encourage the curious readers to look into it. There’s also this diagram to showcase some similarities and differences between the two protocols.

engineers often try to come up with technical solutions to human problems

We have these components:

- the core banking system: the layer responsbile about tracking accounts, accounts creations, updating deposits / withdrawals. When you visit your bank branch, that is thin layer over the core banking system. Some of these are archaic systems being maintained (?) for years

- the payment switch: the switch is responsible for routing payment information between the various entities: it connects with the card scheme (visa, mastercard), which then connects with the issuer bank, and back again to the switch to connect to the scheme -> to the merchant account. We are talking about a routing system if that can relate to backend engineers.

- usually the layer between the switch or the gateway usually is secured behind a VPN and it uses iso8583 protocol.

- the cbs varies, but we it can be a combination of proprietary solutions with SOAP / XML, over regular http, and hence the need for VPN.

- between the point of interaction (POI), the POS and the switch or the payment gateway the communication is mostly via iso8583 with shy efforts to fully replace that with ISO20022. Some payment processors, payment gateways, use a VPN network to communicate between the POS and the network, some use even a VPN with Secure Access Module (SAM) chip (a la SIM card) for securely authenticating the POS to the payment gateway, third use APN (Access Point Name) to connect to the payment gateway, and again the APN credentials would be shared securely (physically handed over to the acquirer, that is the merchant’s fintech company that is responsible about the software) – some use combination of any or all of the before. We are not here in the context of endorsing or discouraging any of the previous approaches mentioned, we are merely just stating the industry norms.

A lot back into the future

Traditionally banks were designed around physical branches. For older readers this might be a familiar sight. If you want to transfer money you’d have to go to your branch, list the recipient information and they would, the teller would ask you for the branch and account ID for the recipient – since, the scale was not of an issue, they would do the lookup themselves and issue the transfer. The teller would then ask you to sign a paper, and then you’d be done. There is indeed extra steps but point is: branches data were siloed, and they were not connected to each other. Moving further, banks expanded in their branches and it became a growth hindering issue to go with this decentralized approach. We then discovered the core banking system, a centralized entity that has everything about the bank account holders, in a central place. The advent towards a centralized model serves an actual utility and helps with actual problems. It is highly advised to review previous attempts before suggesting enhancements. It is also very important to understand how banks operate, and what they value most. The core banking system helps with organizational challenges to the banks and that’s why the often overlooked centralized model is more convenient to the people with the final say, the bankers.

There’s a divergence between formal regulations (or “de jure” rules) and informal norms or practices (or “de facto” standards).

Point to Point Encryption and E2EE

An enticing but not largely deployed technology is Point to Point Encryption. P2PE is a fancy way of saying that financial information is encrypted at each point, starting from the POS (Point of Interaction, POI) all the way to the payment processor, where the data will be decrypted with the aim of Hardware Secure Module (HSM). In one of our previous works, we were trying to deploy a card reader solution and as per the shared specifications, our solution felt to be compliant. We were doing a software encryption and from there, from the POS all the way to the payment processor the payload was encrypted. Eventually, the payment processor delegated the whole case to the regulator and the regulator deemed our approach to be non-compliant. Payment has nuances. We as developers are adept to https, especially younger generations of developers. I remember when I first started learning coding everything was http only, before recently https became the norm.

Why not just https? Wouldn’t that helps everything payment?

That is it actually. We could use https for everything and it’s as secure as it could be. And while https offers the utmost level of security to ensure that the financial message, the payload, is encrypted and secured at transmit, it doesn’t really help at all to ensure that the transaction was in fact made from the authorized party. The same way that, when you click on https://facebook.com/adonese10 you wouldn’t actually be authorized to access my account just because you are using https. That’s why you use username and password to access it. And with the advancement of technology even the mere password username combination is not enough. We discovered the need of a second factor authenticator.

Security is the game of cat and mouse

So, the typical password:username combination didn’t work and we had to discover 2FA or two factor authentications. Dictionary-based and similar brute-force attack made it just with sufficient coding skills, it was not at all difficult to hack into an online account. That was the time where the world was heading to Internet Banking: a new concept that promised to radically change the way we bank by banking using our computers. But before we dive deeper into that world, let’s stumble upon the wonder world of 2FA and MFA.

Something you know, something you have, something you are

Historically, the authentication process as we explored earlier started with the something you know which was just your password. At that time, payment industry had more robust infrastructure for authentication in terms of something you know (your pin), and something you have the card itself. However, when we went online with the ecommerce and the failed promise of internet banking: the payment industry had to fallback to the same security levels as the rest of the internet, the something you know only – while actively trying to educate the customers to not share their cards with anyone.

.

.

When was the last time your account got hacked? Remember those sketchy facebook posts: hey fellas sorry my account got hacked? Welp. Social media and people spending more time on the internet had a huge positive net affect on the internet security. The first was https everywhere and then with the introduction of SMS verification: the something you have. SMS was cheap, it was greatly scaleable. The cost of SMS is technically a zero (I read on hackernews years ago that: sms can be sent over a control channel, which is often used to register your phone to a cellular tower, setting up and disconnecting calls – so it is always on, and SMS can be sent within that channel.). But SMS is susceptible to SIM swapping.

There are two types of attacks: random attacks using bruteforce, dictionary-based and the likes. And then there are targeted attacks. SMS helped with the random attacks, and made targeted attacks more difficult

The last topic that we shall briefly introduce here and then later expand on is the something you are. Biometrics. These are the most secure form of authentication, and most difficult to hack. While reading this article, you might find it a nobrainer to open your bank account via a video-selfie, and access it via your device PIN, fingerprint, and FaceID. They have became synonymous with security.

More recently, we became adept to carry over our mobiles almost all the time, everywhere. Mobile devices have also gain considerable improvements over the years to become the industry standard in terms of security. Modern mobile devices have actually acquired PCI DSS licenses to be used as a POS (you can use your iphone or android to purchase and authorize transactions in a POS, or a website.) What mobile devices offer more is the biometric aspects of them: now we have something that is so unique to only and only match you.

Every fingerprint is unique, so it’s rare that even a small section of two separate fingerprints are alike enough to register as a match for Touch ID. The probability of this happening is 1 in 50,000 with a single, enrolled finger. ~ Apple

And for FaceID

The probability that a random person in the population could look at your iPhone or iPad Pro and unlock it using Face ID is less than 1 in 1,000,000 with a single enrolled appearance whether or not you’re wearing a mask. ~ Apple

We will get back to the something you are. But this so far shall set the stage for what to come next. More often than not, I notice a trend where developers cannot really relate between the regular coding and “fintech coding”, my idea here is to try and gap this bridge. As the case with security, there is always an ongoing research on new methods to mitigate against more sophisticated attacks. One interesting takes are:

- Risk Based Authentication and Behavioral Usage Authentication: this actually deployed to some degree in iphone, where you can see a random pop up to remind you to enter your iCloud password, or in Google where it logs you out and asks you to reenter your credentials. While they are two distinct approaches, in practice they are often used together.

- Signing and verification: We will back to this because there’s some foundational knowledge we are yet to introduce.

Something we are exploring with Sharik – Risk is innate to each transaction

Sharik is Coop Foundation non profit. Sharik offers programs for community based cooperatives, among other activities. Sponsored by diffeent International NGOS, Sharik is planning to launch and Identity Verificaiton System to help with the collapsing state in Sudan. The key word here is identity verification and what it entails.

Risk is innate to the payment transaction. We spoke tentatively about How To Design Bad Systems. You cannot fight fraud, but you could model the risk associated with the parties involved, and let the parties decide whether they are okay with that.

Here’s a simple classical flow for payment. Tip: please you can click to enlarge the figure.

We would like to derive the formula that every transaction is composed of a risk factor. Historically, a merchant would almost always bear all of the costs plus an extra chargeback fees (we will talk about it in a bit). The idea was to always incentivize the consumers since they are ones driving the whole industry. The cost on the merchant is the refund + any operational costs (man hours, filing complaints etc) + a between 20-100$ penalty on the merchant. So, some estimates the refund of a $100 is around $250. That’s a lot, but also largely exaggerated. Another consideration is that Visa allows up to 1% of monthly chargebacks upon merchants before imposing limitations on the merchant (high risk profile merchant, extra processing fees to name but only a few) – same applies to mastercard.

*It is good to point out the clear but subtle for some, differences between purchase and peer to peer transfers: Purchase is when you buy a good from a merchant, in our case via a POS. It is always protected by consumer protection laws, and it allows you “return” the good and get a refund. This is the most important thing. Whether the purchase was made through online or offline. Peer to Peer transfer is as if you give away cash to a friend of yours, you cannot ask any other person to help you get that money back, but you can go to your friend and ask them to return it. When you make a p2p transfer it is usually a final transaction that cannot be reversed, that’s why you’d be prompted to “Add a Beneficiary” first.

If we were to visualize the actual flow, it will look something similar to this

An extra check is being made by the payment processor to

Now, we have also included a risk-based authentication factor too. A merchant can opt-in to processs with a high-risk transaction without asking for a PIN or an OTP (while that is discouraged, and might subject the merchant to a chargeback in addition to penalities from their network processor, it is good to point out the possibilities to aim the product managers, developers and entreprneurs in their fintech journey).

At Sharik, we are ideation the possibilities for a centralized identity management system. The really first rather undated version was OpenID, we had a conversation with Samir Surag and at that time I was independantly tinkering with Blockchain and was caught by how far one can go decentralized and more concretely how one can utilize a rather more robust way to authenticate users via seed and words mnemonic. We have not really achieved any progress past an initial meeting, but the idea remained enticing. Now Sharik is a complex organization and it means different things to different people in our case our focus is on Sharik Toolbox and Sharik SACCOS units.

Most of what we do (the case is extremely very obvious with credit cards type) is that we move debt (risk), and we get rewarded in terms of fees in exchange for that. That’s why the issuer bank (card holders bank) usually takes the majority of the fees! Because they do the 1/n - Thread link

Now, mapping all of that to the payment industry

With the advancements of technology, and the era of internet has kicked it, it was imminent to find alternative ways to authenticate transactions, a la card not present transactions.

Now, remember we used to have:

- the VPN network

- the physical card itself

- DES and symmetric encryption

- the POS

Losing the card-present requirement renders our whole system useless in terms of security.

Anatomy of payment cards

Remember this is actually how your cards look like:  , it is only just 16 digits – it is not necessarily something you can guess; but also not very hard to “accidentally take a picture of it off of your friend”.

, it is only just 16 digits – it is not necessarily something you can guess; but also not very hard to “accidentally take a picture of it off of your friend”.

A Visa card number typically has 16 digits, and they are structured as follows:

Major Industry Identifier (MII): The first digit of the card number, for visa it is 4 – that’s why for spotty readers you can see some forms would turn into Visa icon even before you finish entering your card number

Issuer Identifier: The next five digits, along with the MII, make up the Issuer Identifier Number (IIN), also known as the Bank Identification Number (BIN). The length of pan varies between 16-19, and in fact VISA increased BIN from 6 to 8 to accomodate the growth of its partner banks.

Account Number: The remaining of the digits, except the last digit, are the individual account identification number. The length of this account number varies by institution. It is often used in conjunction with the IIN/BIN to identify the issuer of the card.

Check Digit: The final digit is the check digit, known as Luhn number, is used as a first line quick check. It is like client-side form validation, if that makes sense.

So, if you have a Visa card number like this: 4123 4567 8901 2349, it would break down like this:

- 4 is the MII, indicating a banking and financial institution.

- 412345 is the IIN/BIN, indicating the specific institution that issued the card.

- 678901234 is the account number.

- 9 is the check digit.

4 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4

x2 x2 x2 x2 x2 x2 x2 x2

8 1 4 3 8 5 12 7 16 9 0 1 4 3 8

Now, if they are greater than 9, reduce 9

8 1 4 3 8 5 12 7 16 9 0 1 4 3 8

-9 -9

8 1 4 3 8 5 3 7 7 9 0 1 4 3 8

8 + 1 + 4 + 3 + 8 + 5 + 1 + 2 + 7 + 1 + 6 + 9 + 0 + 1 + 4 + 3 + 8 = 71

Now, we take the modulo of the sum

71 % 10 = 1

Now, we subtract the modulo from 10

10 - 1 = 9

9 is the check digit

None of that really matters that big and can be frankly ignored. But, I’d like to once again explain the elegancy of these systems. Work of art. Point to take home: if you are developer, you might as well get some inspirations from this. If you are a user then you be warned about your cards security.

Types of cards and the principle of least privilege

A very fascinating new OS design is called Fuchsia. It is a microkernel OS, and it is built with Rust. It is a very interesting project to follow. You can check the project here link to Fuchsia OS

Contactless or more commonly tap and go is gaining huge traction and being extensively used by acquirers and fintechs in the last years. The usability of it surpassed any other method and it truly helps merchants acquire more customers. And it totally relates to Fuchsia design here as well: Fuchsia came up with two interesting design choices, they don’t have a concept of a sudo and secondly pretty much apart from the system startup and bootstrapping is handled in the user space. Now, with contactless cards a merchant won’t ask you to provide your PIN at all, you just tap your card and violla you’re good to go. You don’t share your pin, you don’t actually even share your card info at all! You only exchange with the merchant a token your card generate to represent your card, the process is called tokenization and it is something we will touch on later on the topic of card not present transactions. We advise the curious users if they are interested into more details about tokenization to read about our published works on the topic link to tokenization, another really good intro is our preface to Visa and MasterCard link to preface. But the idea is that: sharing PIN over the wire has two big issues:

- the issuer bank and the user; in that the card holders are subject to frauds

- and the acquirer and the merchants; the merchants are subject to chargebacks You can think of the PIN as synonym to the admin password that you would enter to run a priviliged command; to authorize a transaction: modern OS like Fuchsia dropped it; and so is the payment industry. Fintech was never alienated from the broader programming and tech industry, in fact the reason for writing this guideline is to help relate familiar programming concepts that developers know and well versed in to the fintech industry.

The world is shifting towards more compartaemntalized systems, and the payment industry is no exception. The idea is to limit the attack surface as much as possible.

There are two types of contactless payments and while they offer the same service, they have different security models:

Contactless payments with cards and NFC only

Whether the contactless payment origin was a mobile, or just a card, there is a common structure for its security model:

- In the contactless payment, a token will be used instead of the payment details. Payment details are Pan, CVV, and expiration date

- A security token (often called cryptogram, and sometimes referred to as fingerprint) is also used in combination with the

Mobile contactless payments

In the case of mobile contactless payments, that is when you add your bank credit / debit card to your mobile’s wallet and use your mobile to make purchases (tap and go), the scheme usually follows this structure. I didn’t dive in much deep into apple’s ecosystem, but this is at least valid for Google’s Wallet: google issues a one-time virtual card only valid for that transaction. A fascinating process happens when you use your mobile wallet to tap and go:

- when you tap with mobile in the pos, Google will initiate the transaction with the payment processor

- Google interacts with the card network generally either Visa Token Service, or MasterCard Digital Enablement Service to issue a random virtual card for the transaction

- The payment processor will then create a token on behalf of your main bank account, and send it across to the merchant. The token is retrieveable by your bank via the payment processor

- The merchant will then send a debit message to the payment processor which includes the token, the amount, and the merchant id

- Your bank with the payment processor will then retrieve your actual bank account details, and charge you the amount

This way your actual bank account details is only ever available to you and the payment processor! Another thing to point out is that payment processors are glorified routing systems. They don’t hold money, they don’t store value, they just connected these different institutions, via different protocols, and through various channels.

NFC cards contactless payments

When it comes to NFC cards, some intrinsic mobile features are lost. Namely the convenience of storing card info in a secure untampered storage. The card as we explored earlier in the card anatomy is composed of a PAN, CVV, and expiration date. There’s also track 2 info and with the recent advents of chip based transactions, EMV Chip cards. Contactless payments is exclusive and only inherent to EMV chip cards: your magnetic stripe card doesn’t support contactless payment. Another important thing is that often practitioners make a distinct between NFC and EMV Chip cards, while in fact the Chip is the most crucial aspect to make contactless payments possible. The NFC is just a way to communicate between the card and the POS. In payment systems, you will often see this phenomomenon where different parts different system components play together to offer extra level of security. Now onto the actual process of contactless payments with cards:

- During the card personalization step, the issuer bank will issue a token to the card, and store it in the card’s chip. The token is a random string that is unique to the card

- In addition to the token, the issuer bank will also issue a cryptogram, which is a random string that is unique per transaction

- The card and POS exchanges transactions data, that is transaction account number (stored in the card), transaction date, amount, and terminal id

- The data is then listed as per EMV specs and create what is commonly called as input list

- The input list is then encrypted via a secret key, that is stored in the card during the personalization process, now the result is an application cryptogram (AC)

- Now, we have everything needed to initiate the transaction. Remember up until now we never made any server request that involves sending data (cards’ data) over the wire. All transactions between the card and the POS are done via NFC, the generation of the cryptogram is done offline within the card itself, with the help of the chip. The whole whole process only ever happens in the card itself, it doesn’t involve not even the POS, well it does involve the POS, but the card doesn’t share these keys nor does the computation happens in the POS. But how does that piece of plastic get to actually perform crypographical operation? WHERE IS THE FUCKING ENERGY! Well, the process of that is what they call inductive coupling. To use Google’s:

Contactless NFC cards rely on near-field electromagnetic induction for both communication and power. When you tap your card at the POS terminal, a small radio frequency field is generated by the terminal. This field induces a current within the card’s antenna, which powers the chip and allows it to perform the necessary calculations for cryptogram generation and other tasks. The amount of energy transferred is minimal and sufficient for the chip’s basic operations. Additionally, the Secure Element within the card is designed to be extremely energy-efficient, further optimizing power consumption.

- When you tap your card, the POS will initiate the transaction with the payment processor, and the chip will receive the needed power so that it can carry over all of those pesky computations

- The payment processor will then send a request to the issuer bank to verify the token

- The issuer bank will then verify the token, and send a response to the payment processor

A no-auth is retrospectively better than a weak auth.

Card Not Present Transactions

We have briefly layed out the foundation for the future payment scheme to come, that is card not present transactions. Card not present are not exactly a new technology, it has been as old as the dot com boom and the growing ecosystem of online payment. As with the case for every payment method, there’s always a compromise between usability and security. For the card-not-present transactions, up until now CVV was in use to authenticate online transactions. And it was made distinct (3 digits) to avoid any confusion to the users with the PIN, and at the same time to offer a combination between something you know (the CVV) and to some degree something you have (welp, if you don’t share you card with anyone, then technically it is a something you have too). CVV has been the industry go-to method for years and until we moved to otp and 3DSecure.

CVV or card verification value relies only on card number, expiration date, and the cvv. All of those are printed in your card, so whomever (you or anyone else) have access to the card, they can make the transactions. If a hacker stole your card, then they can make whatever purchases they want. CVV doen’t really authenticate the card holder, it only authenticates the card. And that’s why it is not a good idea to share your card with anyone.

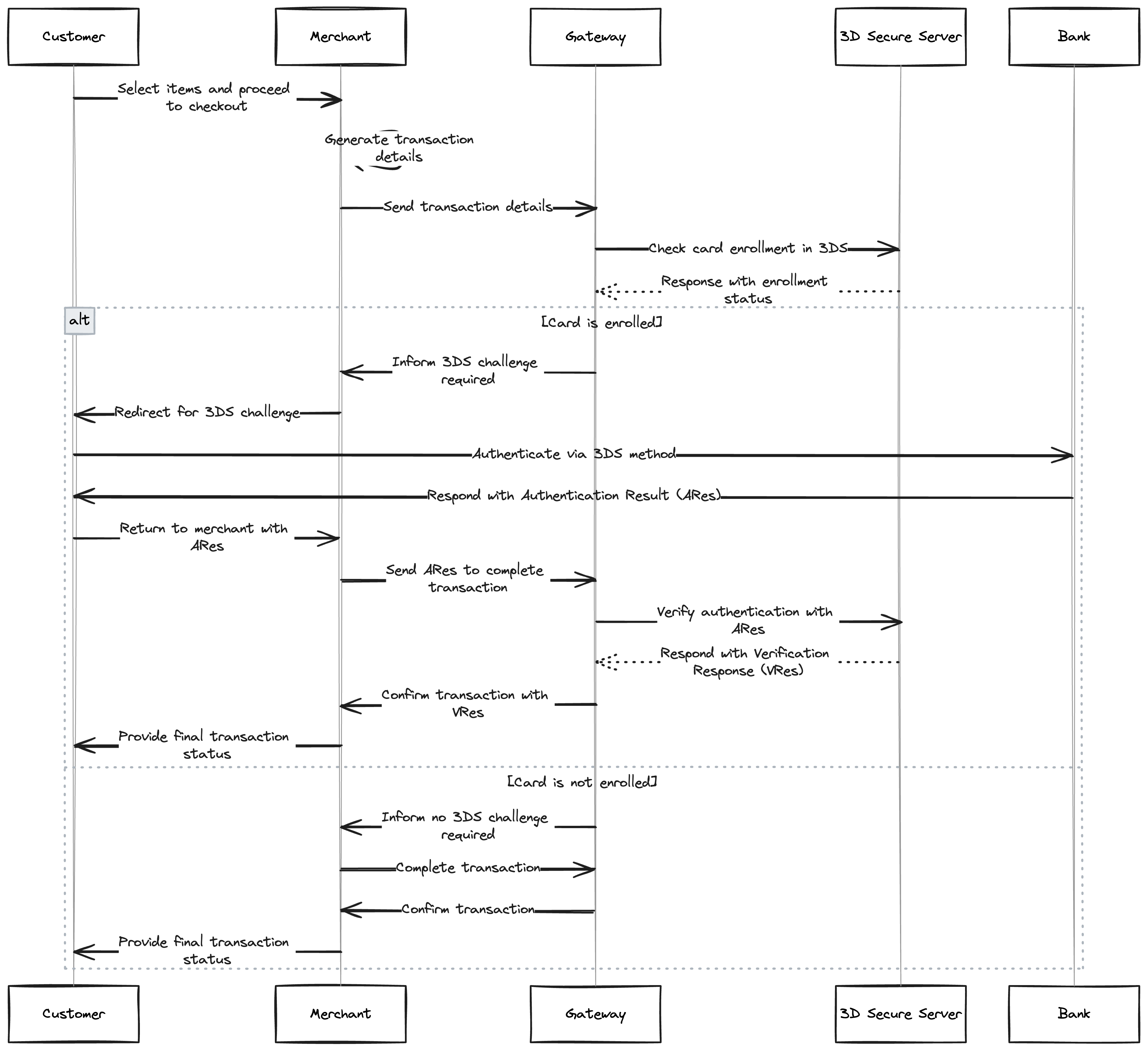

3DSecure on the other hand offer a more robust way to authenticate the card holder info, while at the same time offer a near frictionless experience. The process starts this way:

- upon checkout, payment details will be sent by the payment processor to the acquirer bank

- the acquirer bank will contact the appropriate card scheme (visa or mastercard), which acts as a routing system a la processor here and contact the issuing bank, with the card holder info

- we are showing the actual flow in the figure below, so make sure to check it, but in the end the issuing bank will send a response that has a url with token for this operation

- the user will be redirected to check the url (a webpage that will have their bank branding and all of that), and then they will be notified about the payment details, in addition to the amount and the merchant details. They will then be asked to enter an otp that was sent to their registered phone number (or a push notification to their mobile banking app), and after they enter the correct password / otp, they will be redirected back to their merchant store

- at the end of the day all of these transactions will be batched and ready for settlement

What are the differences between payment processors and card schemes?

As we noticed in the flow earlier a certain overlapping between the card schemes and payment processors, and you wouldn’t be blamed for it. Payment processors are the software and technology providers that offers the solution for all of the payments stakeholders to effectively interact with each others. They are not really banks, and nor they actually do the process of moving money, they are facilitators between all of these participants. Card schemes on the other hand, while they do do some facilitating between acquiring and issuing banks, they set the rules and standards for cards transsactions (also the fees), as well as handling the clearing and settlement of the transactions. They are not actually move funds between banks, but notify them acquiring and issuing banks for said transactions.

At the end of the day, the payment processor’s software in that was used to power the transaction would batch upload all of the transactions onto the acquiring / issuing banks, via the card scheme. Neither the payment processor nor the card scheme actually move funds between banks, and the actual settlement process is either held via a central bank, or a correspondent bank.

Remember in the payment, we always have to make tradeoff between security and convenience.

For card not present transactions, usually the cited figures for fraudlent transactions are 0.08% - 0.13% – they are no exact figures they might go up and down (for example: visa and mastercard have between 1% to 0.6% chargeback before putting the merchant under more stricter, and hence higher processing fees.)